A New Window on Star Formation History of the NSC at the Galactic Center

Publication: The Star Formation History of the Milky Way’s Nuclear Star Cluster

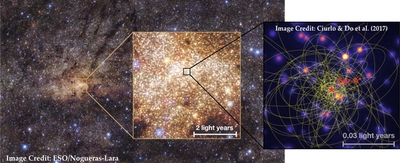

Given its proximity, the Milky Way Galactic Center provides a valuable opportunity for studying phenomena and physical processes which may be happening in many other galactic nuclei. The innermost region of most galaxies is occupied by a spectacularly dense and massive assembly of stars, which forms the nuclear star cluster (NSC, Figure 1). The star formation in this region is believed to be affected by the central SMBH, but the physical mechanisms behind it are not entirely known. The Galactic Center provides a unique opportunity to resolve the stellar population and to study its composition and star formation, and also allows us to predict the number of compact objects.

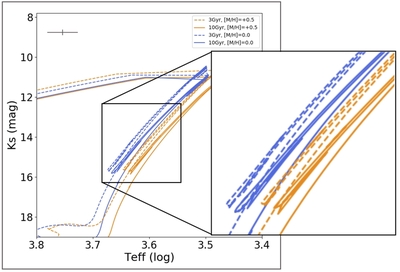

The limitation in our current understanding of the NSC star formation history is that previous studies assumed that all stars have solar metallicity. However, age and metallicity are degenerate parameters in star formation histories (Figure 2); by ignoring the effect of metallicities, the age estimates can be biased. Recent spectroscopic surveys showed a significant spread in the metallicity of stars in NSC, which motivates us to revisit the star formation history and its implications on NSC’s formation and evolution.

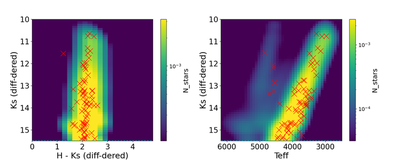

In this project, I present NSC’s star formation history for the first time with metallicity constraints as obtained from a large sample of stellar metallicity measurements from Keck, Gemini and VLT. I developed a Bayesian inference methodology to derive NSC’s star formation history and global properties from photometry and spectroscopy of 770 late-type stars. I apply a forward-modeling approach and a Bayesian framework to derive properties using simulations of synthetic clusters while accounting for observational uncertainties, completeness, degeneracies between properties and stellar multiplicity. I have successfully established a 3-d cluster modeling tool (Chen et al. 2023a), that for the first time includes measurements of K luminosity, colors, effective temperature (Teff) and metallicity. This tool improves the constraints on NSC’s age, metallicity distribution and initial mass function (IMF). I contributed to the open source Python package SPISEA (Hosek et al. 2020) with metallicity interpolation in generating clusters, and the first function of star formation history modeling.

RESULTS: Roughly 90% of the stellar mass formed ~3.6 Gyr ago and is metal-rich (metallicity [Fe/H]=0.45), while the remaining 10% stellar mass formed ~0.6 Gyr ago and is metal-poor ([Fe/H]= -1.05). See Figure 3. The star formation history of the NSC favors a canonical IMF (Salpeter 1955) for late-type stars. Previous studies, assuming a solar metallicity for all stars, reported that ~80% of stellar masses formed more than 5 Gyr ago (Pfuhl et al. 2011). I performed a cluster modeling with fixed solar metallicity and the results yield an age of 7.1 Gyr. If the cluster is assumed to be solar metallicity, the age of the cluster would increase by a factor of two (Figure 4). By including metallicity as a parameter, our models are able to account for stars that were previously difficult to fit, such as low-temperature red giants.

![Figure 4: 1D posterior probability density functions for fittings on the age and metallicity of the ancient burst (bulk mass). Top panels: With the cluster metallicity being constrained from stellar metallicity measurements, the bulk stellar mass was modeled to be 3.6 Gyr with [Fe/H]=0.45. Bottom panels: Fixed solar metallicity modeling yields an age of 7.1 Gyr, which is twice as old. The NSC is modeled to be half as young (~ 3 Gyr younger) if including metallicity constraints.](/post/project2/agefehfit_hu7c8c9b4c2ec17a49a1c028045ef20678_734736_4ae4205dfad7e6a5b0f3e48a670d72dd.jpg)

Our reported younger age would challenge the mutual evolution of the NSC, the SMBH and the bulge (e.g., Graham & Spitler 2009), and may also challenge the formation scenario of infalling globular clusters (e.g., Gerhard 2001; Paumard et al. 2006) due to insufficient accumulation time.

This work contributes to the most accurate predictions of the number of compact objects at the Galactic Center, and the rate at which they merge, releasing gravitational waves detectable by laser interferometers such as LIGO (e.g., Petrovich & Antonini 2017; Hoang et al. 2018). Of particular note: the predicted number of neutron stars, when metallicity measurements are included, decreases significantly (by a factor of 3) compared to earlier predictions, based on the assumption of solar metallicity (Figure 5). This reduces the so-called “missing pulsar problem” (e.g., Johnston et al. 1995; Bates et al. 2011; Torne et al. 2021) and presents a more accurate description of the compact remnant population at the Galactic Center.

![Figure 5: IMF and metallicity are crucial cluster properties to measure for predicting the number of compact objects and their gravitational wave merger rates at the Galactic Center. High metallicity of the NSC, modeled in this project ([Fe/H]=0.5, **Chen et al. 2023a**, yellow), predicts 3× fewer neutron stars (Left). A top-heavy IMF (α=1.7, Lu et al. 2013, red) predicts ~ 3× more black holes, 2× more neutron stars (right) than that with a canonical IMF **(Chen et al. 2023a)**.](/post/project2/numcomp_hu535661bce2c742bf7a0f6a055ac0b6d1_1023836_d298cebeaf334fc4535e7341ca460734.jpg)